By Amy Castor and David Gerard

- You can sponsor our efforts to produce more work like this. Here’s Amy’s Patreon and here’s David’s. For casual tips, here’s Amy’s Ko-Fi and here’s David’s.

- Help our work: if you liked this post, tell just one other person.

Christopher Harborne, who owns 12% of cryptocurrency exchange Bitfinex and stablecoin issuer Tether, is deeply upset at the Wall Street Journal for a story naming him in connection with Tether and their banks. As we covered previously, he is suing the Journal.

Harborne’s lawyers have contacted other media outlets — and even individuals over their personal blogs! — demanding they take down statements on Harborne that cite the WSJ story.

Mr Harborne’s upset is genuine. But by publicly filing a defamation claim and then getting news stories and even personal blog posts deleted with letters from his lawyers, his lawsuit and the actions surrounding it have themselves become serious and noteworthy matters warranting public discussion.

So what’s happening here?

Christopher Harborne promotional photo

Legal threats against media outlets and personal blogs

The Wall Street Journal published “Crypto Companies Behind Tether Used Falsified Documents and Shell Companies to Get Bank Accounts,” on March 3, 2023.

Harborne contacted the WSJ nine months later, in December 2023, and they edited the story on February 21, 2024, adding a note to the online version detailing the edits. [WSJ, archive of February 25, 2024, archive of March 3, 2023]

Harborne got the edits he wanted — but that wasn’t enough. On February 28, he filed a defamation suit detailing the statements that the WSJ had removed. The complaint is filed in Delaware, where WSJ’s parent company Dow Jones is incorporated. [Complaint, PDF, archive, archive]

Harborne’s lawyers, Clare Locke LLP, sent letters referring to the suit to various press outlets and private individuals via email and FedEx. Several sites edited or took down their stories related to the WSJ story:

- Matt Levine edited his Bloomberg newsletter without leaving a note. [Bloomberg, archive of March 18, 2024, archive of March 7, 2023]

- David Rosenthal edited his blog post, leaving a note. [DSHR, archive of January 10, 2024]

- Dirty Bubble Media edited his blog post, leaving a note. [Dirty Bubble, archive of November 30, 2023]

- New Money Review, Unchained, Protos, and CoinGeek completely deleted their stories on the subject — though these were substantially just reblogs of the WSJ story. [New Money Review, archive, archive; Unchained, archive; Protos, archive]

The claims deleted from these stories are all detailed in Harborne’s complaint.

While it’s plausibly reasonable to want an allegation about you that you consider defamatory removed from the web, the lawsuit contains all the claims. This present complaint is an obviously newsworthy public document put there by Harborne himself. It was not filed under any sort of seal. It’s been available to the world for the past month, and will likely stay that way.

Who is Christopher Harborne?

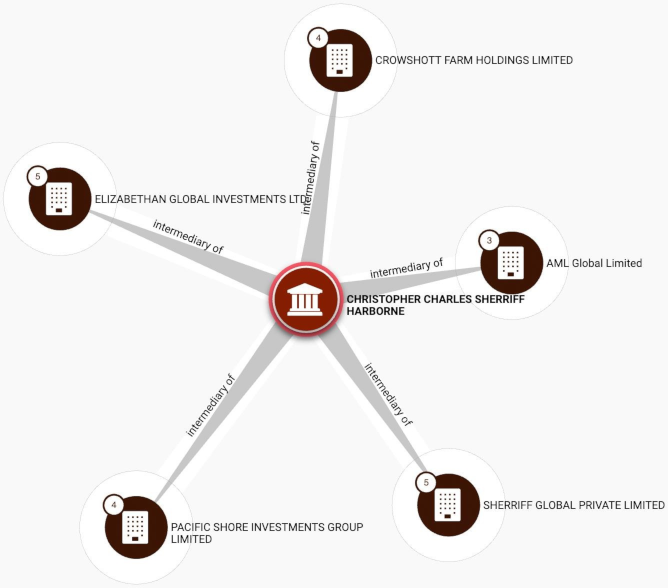

Christopher Charles Sherriff Harborne is a British businessman who lives in Thailand and holds citizenship in both the UK and Thailand. He also uses his Thai name Chakrit Sakunkrit for business.

Harborne has ownership stakes in several companies. He is the owner of AML Global, a jet fuel company. He is the CEO of Sherriff Global Group, which sells private planes, and he is the sole owner of IFX Payments, a British company that moves large sums of money around the globe. He is the single biggest shareholder of UK defense contractor QinetiQ, which was previously the research arm of the Ministry of Defence. And in 2021, he purchased assets of the bankrupt Eclipse Aerospace for $6 million. [Aviation International News]

A keen amateur aviator, Harborne crashed a microlight plane into his neighbor’s garden in 2008. [Daily Mail, archive]

Harborne got into bitcoin in 2011. He says that most of his net worth is in Ethereum. He is a major shareholder of Bitfinex and Tether. As Chakrit Sakunkrit, he is listed alongside CFO Giancarlo Devasini for two Bitfinex corporate entities — Bitfinex Biz Limited and Bitfinex Tech Inc — which Bitfinex used to obtain regulatory licenses in the Bahamas. [SCB]

Harborne donates substantially to political causes, such as the UK Conservative Party — he is one of their largest donors since 2001 — and the Brexit movement, with £13.7 million donated to Reform UK. Recipients of his donations largely appear to be fellow crypto supporters. [Protos, 2019; New Statesman, 2023; OpenDemocracy, 2023]

His significant political donations have made him a legitimate subject of public attention. In 2018, the Red Roar discovered his British name in the Panama Papers linked to five companies. [Red Roar, archive]

The Wall Street Journal stories

The WSJ got hold of what it described as a “cache of documents” related to Tether’s banking efforts. Harborne’s complaint states that this included “internal Signature Bank documents, including the documents submitted in the account application process.” Journal reporters also spoke to unnamed sources at Signature Bank.

Based on that information trove, the WSJ published two stories.

On February 2, 2023, “The Unusual Crew Behind Tether, Crypto’s Pre-eminent Stablecoin,” written by Ben Foldy, Ada Hui, and Pete Rudegeair, introduced Harborne as one of the four major shareholders of Tether. [WSJ, archive]

A second story in March — the one that Harborne is suing over — was about Bitfinex and Tether’s efforts to find banking. This was written by Foldy, Hui, and Robert Barry.

Most of the material in the March story is well-known history and will be familiar to anyone who’s read our writing about Tether over the past few years.

Bitfinex and Tether’s banking problems began in April 2017, when Wells Fargo stopped processing US dollar wire transfers from the companies’ accounts in Taiwan. This cut them off from the US dollar banking system. We know this because Bitfinex tried to sue Wells Fargo, though it withdrew the suit almost immediately. [Complaint, PDF]

Soon after, Phil Potter, then an executive at Bitfinex and Tether, let slip that Bitfinex had resorted to what he called “cat and mouse tricks” with banks — setting up accounts under different business names to shuffle money around the globe. [YouTube]

To find a workaround to get US dollars in and out, Bitfinex and Tether turned to Panamanian money transmitter Crypto Capital. In August 2018, roughly $850 million of customer money that Bitfinex had handed to Crypto Capital based on a handshake — they had no written contract — became inaccessible, frozen by the authorities.

Bitfinex secretly dipped into $650 million of Tether’s reserves to meet customer withdrawals. As a result, tethers (USDT), which are supposed to be backed 1:1 with US dollars, were only partially backed. This got the companies sued by the New York Attorney General in 2018, and ultimately barred from New York entirely.

The WSJ story also pulls from a 2020 affidavit from when the US Department of Justice seized cryptocurrency in the dismantling of three terrorist financing cyber-enabled campaigns. [Justice Department; affidavit, PDF]

New material comes at the end of the story. The last five paragraphs — now edited out — introduce Harborne’s company AML Global, which opened an account at the now-defunct Signature Bank in January 2019 using Harborne’s English name — not his Thai name Chakrit Sakunkrit.

That’s important because, according to the original version of the WSJ story (and quoted in Harborne’s complaint), “Chakrit Sakunkrit” had been added to “a list of names the bank felt were trying to evade anti-money-laundering controls when the companies’ earlier accounts were closed, but Mr. Harborne’s hadn’t.” Harborne asserts that this claim is “baseless.”

The WSJ removed all five paragraphs. Per its note on the current version of the article — also quoted in the complaint — this was “to avoid any potential implication that AML’s attempt to open an account there was part of an effort by Tether, Bitfinex or related companies to mislead banks, or that Harborne or AML withheld or falsified information during the application process.”

According to the WSJ’s sources, Tether and Bitfinex had attempted to open accounts at Signature in 2018, but the bank closed the accounts. US banks at this point were wary of touching any money related to Tether.

Harborne told Signature that the AML Global account was for trading crypto on the Kraken exchange.

WSJ quoted a statement from a Signature compliance executive in one of the documents they reviewed (a quote repeated in the complaint): “If they are buying/selling with Kraken, why is the money only coming in from Bitfinex?” The source said that when it appeared that the account was getting huge inflows of money from Bitfinex, compliance officers at Signature shut down the account. Harborne specifically denies that any money came into the account from Bitfinex.

Defamation by implication

To win a defamation case in the US, you have to prove that a false statement was made about you, that it was reported to another person, that doing so was at least negligent, and that it caused you damage. [Cornell]

The key points are the provably false statement and the actual damages.

Harborne is suing for direct defamation — but he is also claiming that you could infer that various negative claims about him were true.

We asked defamation attorney Andrew Stebbins, a partner at Buckingham, Doolittle & Burroughs in Ohio, about how this works. Defamation by implication is a possible cause of action in some US states — including Delaware.

Defamation by implication is extremely difficult to show in the US. “You have to prove what that implication is and that a reasonable person would understand that the statements you identify are implying what you say they are implying,” said Stebbins.

The “reasonable person” standard is an extremely murky area, he said. “You’re parsing language here and then trying to get into a third party’s mindset that is not there to testify.”

Defamation by implication will also lead to some serious probing on the defendant’s part. “Once you get into discovery, the defendant is going to want to start looking around at your background or your financial information or to get more information to try and prove that their statement was actually true.”

Suing the media

Harborne is bringing suit against a well-funded media entity that will almost certainly have run the original stories past multiple layers of editorial and legal review. This will be a difficult fight to win.

Newspapers in the US have particularly strong protections against defamation cases under the First Amendment — especially after New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, the landmark 1964 case defending journalists from defamation suits brought by politicians.

“Any lawsuit against a media entity is going to be very difficult because you have to show the standard that they published the statement with actual malice — that they either knew it was false or they were so glaringly reckless in their publication that they should have known it was false when they published it,” said Stebbins.

“And so a lot of times in media cases it gets very tricky because if the reporter or the author of the story has a source or some other documentation or something that might even be a little suspect but ultimately stands for what they are reporting on, then it becomes very difficult to say that they should have known that what they were saying was false.”

US jurisdiction includes particular protections for journalistic sources — the reporter shield. “If there was a cache of emails that they came across, those will be discoverable subject to certain redactions. Ultimately, the judge would probably get involved in ruling on the disclosure of an informant, a witness, or a source,” Stebbins said.

The complaint

Harborne says that the WSJ accused him and his company AML Global of “committing fraud, laundering money, and financing terrorists”.

The WSJ doesn’t make these claims. Harborne’s argument is they could be implied from the story — because AML Global is mentioned along with all of the legally problematic things Tether has done, which they eventually settled over with both New York and the CFTC.

The crux of the 86-page complaint is that Harborne did not lie to the banks by omitting information — such as his other name, Chakrit Sakunkrit, and his involvement with Bitfinex and Tether — and that the WSJ implied AML Global was a mere “shell company,” not an operating business entity.

Harborne tries to show actual malice and carelessness: that the WSJ was out to get him and that the reporters were irresponsible. If he can demonstrate that the WSJ lied deliberately and/or had contempt for the truth, this would enormously help his defamation action.

The WSJ reported that in the bank application, Harborne did not list his Thai name. His stakes in Tether and Bitfinex are held in the name Chakrit Sakunkrit, according to both the WSJ and the complaint.

Harborne says he did disclose his Thai name — not on the account application itself, but “during Signature Bank’s due diligence process weeks before the account was ever opened.”

Thus, the Journal knew that the very documents it reviewed and on which it reported in its defamatory Article conclusively disproved the false accusations it intended to publish about Mr. Harborne and AML before it published them. But the Journal published those accusations anyway.

The Journal also said that Harborne did not tell the bank about his links with Bitfinex and Tether. Harborne says that’s inaccurate — the bank just didn’t ask.

This next part appears to be arguing with Signature, rather than the WSJ:

And further demonstrating that neither Mr. Harborne nor AML sought to hide anything from Signature Bank, AML Global Payments LLC and Mr. Harborne offered to provide the bank with Mr. Harborne’s résumé or a biographical statement, but the bank did not take them up on the offer.

Harborne says he initially inquired about opening a bank account at Signature in November 2018. Coincidentally, this would have been just after Crypto Capital accounts under the control of Bitfinex money mule Reggie Fowler had been frozen.

Because AML operates in hundreds of locations throughout the world, it is highly vulnerable to currency fluctuations — a problem that Mr. Harborne expected cryptocurrency could help ameliorate. Thus, in November 2018, AML Global Payments LLC contacted New York-based Signature Bank to open an account to use to trade cryptocurrency.

He then opened the account in January 2019 “to trade stablecoins through Kraken.” He says the account “barely” got any use and only had about $15 million it in at one time — money that was wired directly from Kraken.

He emphasizes multiple times in the complaint that the Signature account had no connection to Bitfinex or Tether:

AML’s Signature Bank account was never used for Tether or Bitfinex whatsoever. In fact, the account was never even used to trade Tether, and it did not have a single transaction associated with Bitfinex.

Hedging with tethers

So why did Harborne open a business account at Signature? He says that he invests in and uses USDT as a tool against foreign currency exposure for AML Global. That is, he is using money he gets from selling aviation fuel to buy tethers.

The usual way for an international business to hedge against currency fluctuations is to buy currency derivatives — particularly a non-crypto company like AML Global. It is unusual to hedge aviation fuel costs using USDT and not just actual dollars, if you have access to actual dollars.

The Signature account was set up by AML Global Payments — a limited liability company registered in Wyoming with offices in California. [Wyobiz]

Harborne says that the payments company is not the corporate entity that deals in aviation fuel and says that the WSJ’s statement that “Signature Bankers were then introduced to a company called AML Global, an aviation fuel broker that was looking to open an account” is “demonstrably false” — even as he states earlier in the complaint that the payment company “handles the receipt of incoming payments and the processing of outgoing payments for AML Global Group’s operations” as part of the group.

Signature sent Harborne a letter on May 8, 2019, saying the account would be closed.

Per the complaint, the bank “expressed no concerns regarding Bitfinex, Tether, allegations of money laundering, or Mr. Harborne’s supposed failure to disclose his Thai name (which he and AML Global Payments LLC had disclosed). In fact, Signature Bank expressed no concerns whatsoever.”

This is likely true — but it’s also meaningless. Banks are not required to tell you why they are closing an account. As the head of two payments companies, Harborne would be reasonably expected to know this.

Committing journalism

Harborne complains that he wasn’t given enough time to respond with a comment before the article went live — only 24 hours. But he admits that they tried to reach out to him and couldn’t get a response. Harborne could easily have supplied a comment after the story was published — newspapers quite frequently add comments to the online version of a story after it goes live. As he says, he didn’t reach out to the WSJ for nine months.

He also says that the Journal went on a “fishing expedition” to dig up more information on him and — quoting from an email the WSJ sent out — “understand as much as we can about Mr. Harborne, his businesses and the sources of his wealth”. Most people would call this “doing journalism.”

Harborne also takes aim at the quality of WSJ’s reporting:

The Article described, in a reckless and scattershot manner, Tether and Bitfinex’s alleged involvement in a raft of financial crimes, including fraud, money laundering, and terrorist financing; stretched its narrative to encompass a Department of Justice investigation, convicted crypto fraudster Sam Bankman Fried, and even Hamas; and then, in its last five paragraphs, shoehorned Mr. Harborne and AML into its salacious narrative without any basis or justification.

This would be very unlikely to be substantive in a defamation case.

Harborne and banks

What does Harborne hope to achieve by filing the suit even after the WSJ edited the story pending investigation? He asks for financial compensation. But we think he also hopes to get his banking back:

As a direct and proximate result of the false Statement published by the Journal, Mr. Harborne has suffered substantial economic damages, including, among other things, loss of current and future business opportunities and the inability to secure regulatory approval from a national bank in order to continue carrying on his business, which provides payment processing services.

Harborne owns IFX Payments. IFX is not named in the complaint — but the complaint does state that the Bank of Lithuania flagged Harborne’s application for regulatory approval for an unnamed “payment processing company” for additional scrutiny, specifically citing the WSJ article. Harborne says that this meant the company could no longer operate in the Eurozone.

He also claims that the story harmed Eclipse Aerospace in a prospective deal with Pratt & Whitney:

For the last few weeks (leading up to the filing of this Complaint), P&W has been postponing a call with Eclipse regarding this venture—and P&W has explained to Eclipse Aerospace that P&W’s parent company, RTX Corporation, has flagged the Journal’s Article as the reason for not moving forward with this transaction and as the reason for postponing the conversation about it. In short, the damage from the Article is quickly, and exponentially, compounding.

It’s not clear to us that this suit will get Harborne’s accounts back. Banks are not generally obliged to take on a customer. If the WSJ’s claims about the document cache are true, Signature was already having considerable doubts about Harborne as a risk factor.

Clare Locke

Harborne has hired Clare Locke LLP, the husband and wife duo — Tom Clare and Elizabeth “Libby” Locke — who have made a name for themselves going after journalists in their role of “representing clients facing high-profile reputational attacks.” [Clare Locke]

Clare Locke is known for sending ridiculously long demand letters to media, such as the 77-page letter they sent to Business Insider on behalf of billionaire investor Bill Ackman about stories alleging that Ackman’s wife Neri Oxman had committed plagiarism. [TechDirt]

When the Twitter campaign Sleeping Giants was approaching Breitbart.com advertisers asking them to stop supporting Breitbart on the grounds of hatemongering conduct and promotion of socially damaging conspiracy theories, Clare Locke wrote a letter to Sleeping Giants founder Matt Rivitz in 2018 demanding the preservation of any communications they might have had with a long list of groups, including “Any and all George Soros-backed persons or organizations”. No suit has as yet been filed. [Daily Beast; demand, PDF, archive]

Libby Locke said in a speech to the Federalist Society that she thinks “the pendulum has swung too far in the direction of freedom of the press.” Locke also wants to roll back New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. [Jezebel; Daily Beast; New York Times, archive; Federalist Society]

What happens next

Harborne got the WSJ to edit its story. But then he filed the suit. This means he is forcing the WSJ to fight him.

There will almost certainly be discovery on all the claims of fact in the story that are disputed in the suit, such as the details of Harborne’s account application. Much of this discovery is likely also to be made public in case filings. Former Signature employees may be called forth as witnesses.

Dow Jones is represented by Young Conaway Stargatt & Taylor. The plaintiffs are represented by Farnan LLP. Elizabeth Locke of Clare Locke notes at the end of the original complaint that she is waiting to be admitted to the case pro hac vice as an out-of-state lawyer.

Judge Kathleen M. Miller is presiding over the case.

No hearing date has been set, nor has a reply been filed as yet. But on March 20, Dow Jones requested a jury trial. The court documents are available via the Delaware Superior Court Civil Case Search page. The case number is N24C-02-292. [Delaware Superior Court search query for the case]

We suspect that Harborne has let his sincere upset lead him into ill-advised tactics. Using reputation lawyers to try to scorch the earth of the existence of allegations from a major news story, down to mentions in personal blogs, is the sort of thing that risks you looking like a bully — especially when you then proceed to publicize the accusations yourself in a lawsuit that is obviously going to be newsworthy in its own right.

We would not be surprised if Harborne reconsidered and dropped the case before trial. If it does go to trial, we’ll be watching closely.

Your subscriptions keep this site going. Sign up today!

I wonder if Harborne’s donations to the Conservative party have had any effect on the UK government’s desire to make the UK a cryptocurrency hub?

The two are a coincidence that others have noted previously, such as Finance News: https://www.fnlondon.com/articles/crypto-lobbyist-donated-500k-to-conservatives-before-uks-crypto-hub-move-20220617

“Christopher Harborne, a Thailand-based businessman, made the payment on 9 February.

The government two months later announced its intention to turn the UK into a “global hub” for the crypto industry.” Here’s the archive of that story: https://archive.is/BBVNF#selection-691.0-700.0

Thanks also to Max Goodman at Amundsen Davis for expert background assistance also.

Wouldn’t the conventional way to hedge as an aviation fuel vendor be… futures on aviation fuel? That is, what IIRC Southwest Airlines used to do?

Sure, aviation fuel prices might be less stable than the US dollar, but aviation fuel is what you actually have to buy and sell in order to run your business.

It is not hedging “aviation fuel prices”, but currency fluctuations in different markets. But, as noted, the normal way to do this would be using currency derivatives.

My point, though, is why an aviation fuel company would need to hedge currency fluctuations in the first place. The value fluctuations that would most directly affect an aviation fuel company would be fluctuations in the value of aviation fuel.

Hedging dollars or pounds when fuel prices are much more volatile than exchange rates doesn’t seem to protect from the actual risk exposure experienced by the company in question. Rather, it seems like a thin pretext for the company’s management to gamble with their revenues.

From what I understand, it is quite common for companies doing business internationally to hedge currency fluctuations, regardless of what that business is. Unless I missed something the info we have says nothing about whether or not the company was hedging fuel prices, so it might very well have been doing so. But it seems to me not at all strange that it might be hedging currencies, as well.

Thanks for the link to the docket.

One of the attorneys filing to represent Mr. A/K/A is Jered Ede. He is a partner, so not just the guy who carries stuff. From his bio the CL website:

“Prior to joining Clare Locke, Jered was the chief legal officer of media non-profit Project Veritas, through which he managed a team of lawyers working on reputational risk. During his time at Veritas, Jered and his team obtained over five dozen corrections and retractions and avoided countless more inaccurate articles”

He was CLO for Project Veritas 2020-2022, For those not familiar w the U.S. right wing media space … intro paragraph from Wikipedia:

“Project Veritas is an American far-right[14] activist[15] group founded by James O’Keefe in 2010.[19] The group produces deceptively edited videos[13] of its undercover operations,[5] which use secret recordings[5] in an effort to discredit mainstream media organizations and progressive groups.[20][21] Project Veritas also uses entrapment[12] to generate bad publicity for its targets,[2] and has propagated disinformation[23] and conspiracy theories[31] in its videos and operations”

So that’s the space this is in. I wonder how long it will take for this to devolve into, I have no pearls to clutch, so I have to say ratf-kery. Which is almost a term of art.

—dj

I did notice Clare Locke’s experience with Project Veritas, a source of information so reliable that both it and James O’Keefe personally have been barred from being used as sources on Wikipedia.

(I was the guy who closed the Request for Comments on Veritas/O’Keefe, but the consensus was overwhelming. First time we’ve deprecated an individual personally as a source.)

That was a good send off at Wikipedia.

He is a perennial weed, allegedly.

What I truly don’t understand is, if Mr. Harborne wants everything unnoticed and out of sight, why did he bring these noisemakers?

I think he waited too long, Tether had reached the point where it’s causing more visible (to the average Joe) damage than the value provided as a “surveillance device” to the State.

He’s going to be covered in it.

—dj

We don’t know why either. Tether has been a bit sensitive lately on all the news its getting on money laundering and sanctions violations. The Feds are paying close attention now. So maybe Harborne wanted to strike back? But also it appears he may be having some banking problems himself, so he wanted to clear his good name.

There’s also the small matter of discovery, which, in his shoes, I would be unlikely to want to go through.