In the wake of Facebook’s Libra announcement, central banks have been talking up the idea of doing central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), to compete with Libra.

Electronic money is mostly issued by commercial banks — as cards for credit extended by the bank, or as debit cards to access money from your own account. But a CBDC will be just like cash, issued directly from the central bank — except electronic.

(Though unlike cash, the proposed CBDCs will be as traceable as cryptocurrency is — the Chinese CBDC initiatives in particular seem quite keen on an all-pervasive surveillance panopticon.)

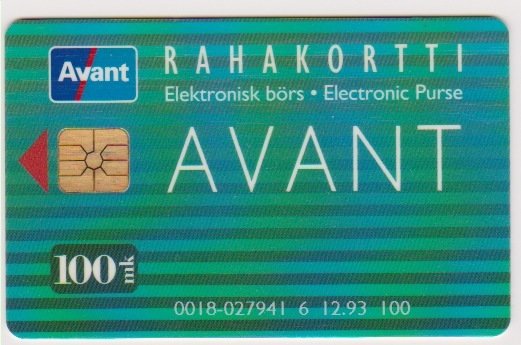

Of course, there are very few new ideas in finance. Aleksi Grym tweeted yesterday about a 1990s experiment in central bank electronic cash — the Avant Card, from the Bank of Finland. [Twitter]

Central banks have been discussing CBDCs for many years. In his day job at the Bank of Finland, Grym and his coauthors Päivi Heikkinen, Karlo Kauko and Kari Takala recount the history of Avant in their 2017 paper “Central Bank Digital Currencies.” [2017 paper, PDF] Other Bank of Finland papers mention the lessons of Avant. [2003 paper, PDF; 2004 paper, PDF]

Avant was launched in 1993, and discontinued in 2006. It was never very popular, because it was annoying and expensive to use — and plain debit cards were just better.

(UPDATE: see at bottom — Grym has researched further and found it was rather more popular than he first thought.)

The Bank of Finland loved the idea — but forgot the bit where the users had to love it too.

1993 100 mk Avant card [Colnect]

Avant for the user

Avant was created in 1992 and launched in 1993 as a phone card — back when that meant making calls from phone booths. Some shops, vending machines, parking meters and buses also accepted Avant.

The Avant card itself was a smart card with a chip on it — it looked very like a current debit or credit card.

Avant was not an online CBDC, as most current proposals are — it was a card containing what was legally electronic money, held in the chip.

Avant cards were originally disposable, but from 1994 onward, they issued cards that could be refilled at any ATM — an “electronic purse.” An Avant card could hold up to 2000 markka (then 336 EUR, equivalent with inflation to 461 EUR in 2020).

It cost 2 mk (then 0.34 EUR) to load or unload the card — or a 5 mk premium on the disposable cards (50 mk card for 55 mk, 100 mk card for 105 mk). Fees on purchases were 1% to 5%, generally paid by the merchant.

By the end of 1997, you could use your Avant card on the Internet, to buy things or to top up the card — though the card reader was expensive, at 390 mk (then 65 EUR). [BIS report, PDF; University of Helsinki Library, translation]

Avant’s ambitions

The “electronic purse” was a very exciting idea in the mid-1990s — exciting to the banks and the technology vendors, at least. Smart Card News ran a feature on Avant in its November 1995 issue. [Smart Card News, PDF]

Avant was run by Toimiraha, which was owned by the Bank of Finland — though the company was later sold to a group of commercial banks (Merita Bank, Okobank and Postipankki), and renamed Automatia Rahakortit.

Avant’s ambition was to set up a single national electronic purse system — the commercial banks would bring their customer bases, and their ATM networks. The Bank of Finland expected that Avant would take over from coins for small purchases.

The Bank of Finland was convinced this system was the way of the future — people like having their money right there in their hands, don’t they? — and was mostly worried about making sure that incompatible competing networks didn’t spring up.

Short-run custom versions by the mid-1990s [Colnect]

The card that never was

Avant never really took off. The biggest problem was that end users were unhappy at being charged a fee for loading and unloading money — or the 5 mk premium on the disposable cards. And people were already used to free ATM withdrawals by this time.

There weren’t a lot of merchants — though Avant did sign up thirteen McDonald’s restaurants. (There was even a McDonald’s logo Avant card for a while.) [Colnect]

Companies tried forcing captive user bases, such as students, onto Avant — but this just caused resentment. [Ylioppilaslehti, translation]

The debit and credit card networks were better and more functional than Avant. Users often had combination cards, with debit, credit and Avant all on the same card — and the debit and credit functionality was used vastly more than Avant. [Twitter]

Avant was discontinued at the end of March 2006, when the lower limit was removed from debit card purchases. [Ilta Sanomat, translation]

Several other countries had similar stored-value card networks — Smart Card News listed several in the November 1995 issue. These mostly didn’t take off either — the debit card network did all of what end-users wanted, and did it better.

(One important exception is Hong Kong’s Octopus card — a travel card that became widely used and accepted. The bank-backed option, Mondex, failed in the market.) [Coercing consensus: unintended success of the Octopus electronic payment system electronic payment system, PDF]

Stored-value cards in 2020 — prepaid cards

These days, you can get prepaid Visa cards and Mastercards, that you can top up. These are mostly used by people outside the banking system — the developed-world unbanked and underbanked — and are only useful at all because they can be used on the existing payment networks.

Like Avant, the present-day prepaid cards also tend to hit the users with fees coming and going — because nobody uses these things unless they have no other options.

Prepaid cards are often available through banks — and bank-issued prepaid cards can provide more consumer protections and lower fees. These are pretty much debit cards with limited functionality. Fintech challenger banks, such as Revolut, offer more sophisticated versions, with monitoring and management.

The back of a 1999 Avant card [Colnect]

Avant’s lesson for future payment systems

User convenience is king.

The existing debit card systems are really very good — they have user take-up, they have merchant take-up, and they’re actually displacing cash — and they give the typical user the reassurances they really want. Did you know that if you lose your card … your money is safe, and not lost? You can’t say that about a £20 note.

CBDC advocacy hasn’t changed since Avant. CBDCs are the sort of thing the vendor loves — but I’ve yet to see the case for consumers.

CBDCs will have to be better than debit cards — for the typical consumer. A technically exciting back end, that gets other vendors to sign on with you, is not enough — your market is users, not other vendors.

You might think that’s obvious — but it’s a lesson that history keeps having to hit technology vendors over the head with, repeatedly.

Thanks to Aleksi for sources and review.

UPDATE: Since the above was written, Aleksi Grym has written a deeper dive into the history of Avant. The system was rather more popular than he thought at first. See “Lessons learned from the world’s first CBDC” in BoF Economics Review, 8/2020. [Helsinki University]

Your subscriptions keep this site going. Sign up today!

To compete with debit cards, at a minimum CBDCs must:

1) Be simple to use and have fast transaction times

2) Enable refunds/charge-backs

3) Allow users to recover funds if private keys are lost

On their own, these criteria are not enough to incentive the move to CBDCs. A government must commit to a CBDC being its currency of choice–taxes must be paid in the CBDC, government contracts and salaries must be issued in the CBDC, and so on.

The future will still be multi-currency, but a mandate requiring all government interactions use a CBDC is a powerful incentive to drive user adoption.

End user convenience IS king –> which is also why pre-paid cards are actually increasingly popular also among the banked: for their interfaces, the way that different kinds of purchases can be grouped and managed and because they can hold several currencies (and crypto) at once (Revolut for example).

those are getting toward elaborations on the prepaid-to-debit spectrum, but yeah

added Revolut

probably not a huge percentage – but, for instance, anyone who has to deal in both pounds and euros routinely, without paying a swingeing fee every time.

What percentage of people need to deal with multiple currencies whose needs are not being met by on-demand buy (letting their bank handle the exchange) or worst case just carrying another card?

But what’s the point of a cbdc anyway?

WELL INDEED

The “holy grail” in the field economics is an accurate model of the economy. The economy is so large and complex that it is difficult to understand all economic implications of policy XX, or to determine the reasons economic event YY occurred.

But imagine if all financial transactions were recorded to a blockchain. One could observe the movement of funds in real-time, and on a granular level never before possible. On a permissioned blockchain controlled by the government, it could tie identities to specific addresses and whitelist/blacklist addresses.

This sort of power could be used for good or evil.. ideally it helps the government make better and more impactful policy decisions, but could also grant the government unprecedented economic control over its citizens.

This relies on the illusion that more data will surely help you – when the problem is almost always that you know damn well what the data say, but the blockage is political.

The promise you’re talking about is what Izabella Kaminska calls Gosplan 2.0. It’s likely to work out about as well.

Japan’s PASMO and Suica stored-value cards are also successful. And there are equivalents in Taiwan, pretty much because Taiwan has to have whatever Hong Kong and Japan have. Imagine if the UK Octopus card became reverse-compatible with any contactless bank terminal – there could be significant uptake. Topping up these things with cash is effectively fee-less, and I might prefer to top it up via a cheap Transferwise transaction (or just bring cash) rather than use my main bank card on a trip to the UK and pay out-of-network fees.

Of course, none of this is CBDC, just a different way of doing debit cards.