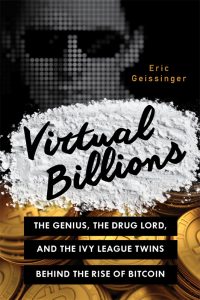

- Eric Geissinger: Virtual Billions: The Genius, the Drug Lord, and the Ivy League Twins behind the Rise of Bitcoin (Prometheus, April 2016 — UK, US)

Written in 2015 and published in 2016, when nobody much cared about Bitcoin. Virtual Billions looks like a history of Bitcoin, but it’s more a collection of historical anecdotes about money and finance that riff off Bitcoin. The strongest theme is libertarianism, what it means for Bitcoin and, in the case of Ross Ulbricht, how badly it can go wrong.

The introduction doesn’t actually introduce the book until its end: the author will attempt to explain Bitcoin through Satoshi Nakamoto, Ross Ulbricht and the Winklevoss twins. But first, he’ll throw in some rambling extended slabs of history of questionable relevance! These digressions continue through the rest of the book.

The worst part of writing a book about Bitcoin is having to explain just what the hell a bitcoin is. Geissinger’s attempt isn’t too bad — apart from the way-too-long digression on the Byzantine Generals problem — and finishes with a nice interview with Emin Gün Sirer on dumb ways to mess up your security and lose your bitcoins.

Geissinger’s admiration of Bitcoin is clear — “the fastest and most technologically advanced method for instantly and securely sending money to anyone on Earth” — even if that particular claim was already jarringly out of date, given the transaction clog and increasing fees and delays were well under way by 2016.

The Satoshi Nakamoto section gets into Nakamoto’s interest in Austrian economics. I’ve found myself arguing more and more of late with Bitcoin fans who refuse to believe that Bitcoin was based in the principles of goldbuggery, libertarianism and Austrian economics. They treat this claim as some sort of leftist propaganda — I guess libertarianism must not be Good News for Bitcoin this year. But the trail is obvious, and Geissinger picks up on it too. It’s the same stuff I cover in chapter two of my book, and that David Golumbia completely nails down in The Politics of Bitcoin (US, UK).

Next is the section on Ross Ulbricht, founder of the Silk Road darknet drug market. Ulbricht’s alias, “Dread Pirate Roberts,” sets Geissinger off on a long ramble about nerd culture, including the history of Atari video games — with 6502 assembly code! — all for the argument that the culture at Atari “functioned as a minor libertarian experiment” and that the Silk Road “took what began at Atari and pushed it to the limit.” This really isn’t a good or useful claim, and this is probably the worst of the book’s digressions.

Ulbricht’s ideological reasons for becoming a drug kingpin are explained, then critiqued. Keep in mind that he never really went for the money — he had a huge stash of bitcoins, but he lived modestly. It’s Ulbricht as utopian idealist — and what happens when you overextend an ideology to the point of monstrosity. “Nothing can be taken to extremes with the confident expectation that it will work in predictable ways.”

The digression into Ross Ulbricht as physicist pays off when Geissinger points out that Ulbricht’s statement of intent — “I am creating an economic simulation to give people a first-hand experience of what it would be like to live in a world without the systemic use of force” — is not science, but pseudoscience: “Ross isn’t wondering what the result will be, he’s telling us what it will be.”

He then takes us through how this utopian idealism led directly to Ulbricht actively seeking out career criminals to murder people he felt had trespassed upon his bitcoins — there’s some fun detail on Ulbricht’s notion of the Hell’s Angels in 2013 as “an honest-to-goodness criminal enterprise capable of executions on demand.” And now he’ll be spending the rest of his life in jail. This is the best chapter in the book. “An evil man who’s completely unaware of his own evil … the ‘grain of insanity’ at the root of every extreme ideology.” It never occurred to him at any point to ask himself: “are we the baddies?“

Geissinger describes the key problem with libertarianism: simplistic answers for those dismissive of and lacking knowledge in the humanities. “Ross was in danger of accepting only those opinions that happened to match his personal, political, and emotional inclinations, unmediated and without an analytic eye.”

We switch mood entirely for the Winklevoss twins. Geissinger’s thesis is that they deserve more credit than they get for holding onto their Facebook windfall, which he credits to a good upbringing by their father, Howard Winklevoss, an expert on pensions — and cue another lengthy historical digression that doesn’t pay off.

The Winklevosses mainstream Bitcoin for Wall Street. We go through their ill-fated involvement with Charlie Shrem of BitInstant, Shrem’s conviction for knowingly laundering drug money for the Silk Road, and their call for increased regulation in the form of the New York BitLicense. “The Winklevoss twins are acting like adults in the still-young market, and are busy getting other adults involved.”

The conclusion can’t quite bring itself to state outright that Bitcoin will surely overcome its glaring technical woes, but alludes to it with a few pages of digression on the phonograph.

The book isn’t really about Bitcoin — it’s more a collection of historical anecdotes, of varying relevance to the topic, with a bit of Bitcoin flavouring. There are too many digressions that are too long and don’t pay off. The multi-page quotations and interview transcripts should have been rendered as prose. There’s not much in-depth history of cryptocurrency. Though chapter five on Ulbricht is a really good slice of true crime that successfully addresses the question of what on earth the guy was thinking.

A general reader will learn a lot of useful history of economics and get the idea of Bitcoin, if you don’t get bored with the sprawling digressions, but I think you’ll be disappointed if you were reading it for the Bitcoin. If you’re a crypto follower, it’ll give you a couple of hours’ long-winded but not unpleasant reading on some history of money, even as a lot of it doesn’t connect to the supposed topic. And, of course, there’s that excellent Ross Ulbricht chapter. Don’t go out of your way for this book, but do read chapter five if you happen upon it.

Your subscriptions keep this site going. Sign up today!